Alzheimer’s Might be an Infectious Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating illness. All to often, the condition robs people of their memory and health as they age. Unfortunately, rates of Alzheimer’s are increasing world-wide. Nearly 5 million people over age 65 currently have Alzheimer’s in the United States—two-thirds of these individuals are women. Alzheimer’s is officially the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. Total payments for caring for Alzheimer’s patients is approximately $305 billion, with out-of-pocket spending reaching $66 billion (Alzheimer’s Association 2020). The costs to our country, our economy, our families and the individuals suffering with the disease is enormous.

For many years, mainstream medicine has been trying to find a game-changing treatment for the disease. While numerous candidates from animal trials have been tested, due to poor outcomes, many failed to reach clinical use. In fact, 99.6% of drug candidates for Alzheimer’s disease have failed in the approval process (Burke 2014). Most drug candidates target amyloid, a sticky plaque that builds up in the brain early in the disease. It’s been widely believed that amyloid causes the damage in Alzheimer’s. Remove the amyloid and you stop disease progression, or so the theory goes. While animal models seemed to suggest these types of results, human trials mostly have not.

Alzheimer’s as an Infection

If the main hypothesis that amyloid buildup causes Alzheimer’s disease is not correct, it would make sense why drugs targeting amyloid continue to fail in clinical trials. For over thirty years, a small but growing contingent of researchers have been putting forward another hypothesis: Alzheimer’s is a disease caused by brain infections (Maheshwari 2015).

The most common infectious organisms implicated in causing Alzheimer’s disease include (Harris 2015):

- Herpes family viruses

- Chlamydia bacteria

- Spirochetes (with lyme disease being a representative organism)

- Other oral bacteria

Amyloid as an Antimicrobial Response to Brain Infection

Animal studies demonstrate that brain infections induce amyloid and other types of plaques and tangles, the main proteins thought to cause Alzheimer’s disease (Little 2004, Wozniak 2007, Miklossy 2006). Research has also, in some cases, discovered these amyloid producing pathogens in the brains of human Alzheimer’s patients, although the findings haven’t always been consistent (Balin 1998, Wozniak 2009, Miklossy 1994).

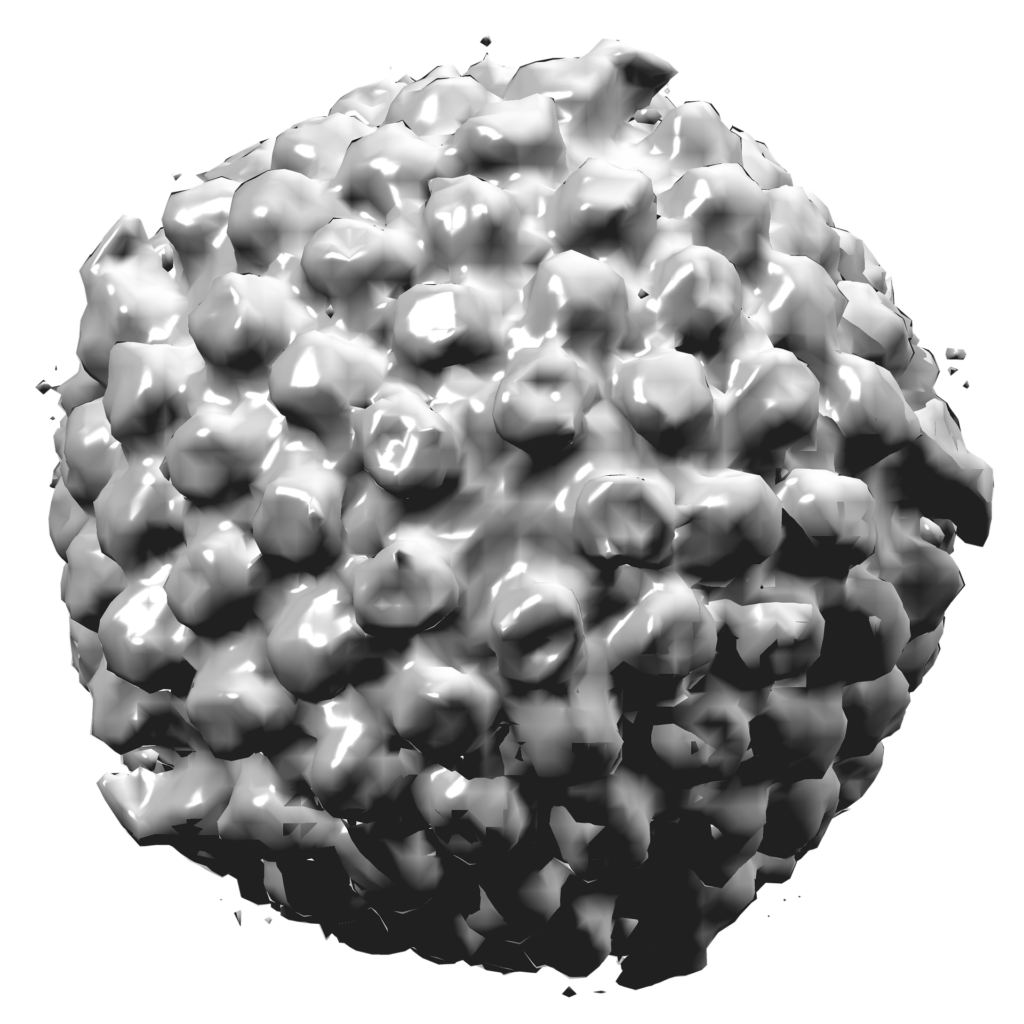

More recent research has also started to demonstrate that amyloid proteins appear to be antimicrobial. Through the production of amyloid, the body is trying to protect the brain from infection (Eimer 2018, Soscia 2010). These proteins trap infectious organisms, but overtime, can build up and damage tissue. If amyloid isn’t the actual cause of Alzheimer’s disease, it would make sense that clearing these proteins would not resolve the condition.

Herpes Simplex Virus and Alzheimer’s

A recent model for Alzheimer’s disease was created through growing brain tissue from human stem cells. This 3-dimensional brain model was then infected with herpes simplex type 1 virus (HSV1). Within days of infection the brain model developed plaques, similar to what is seen in Alzheimer’s. In addition, enzymes and inflammatory components seen in dementia were also induced. A fulminant HSV1 infection alone was able to rapidly induce Alzheimer’s-like pathology in a realistic human brain model (Cairns 2020).

A large retrospective study out of Taiwan showed that HSV infection increased the risk for dementia by a factor of 2.5. Among patients infected, a percentage of them used antiviral medications for treatment. Those that used antivirals decreased their risk of developing dementia from 28.3% to 5.8%. Antivirals, in HSV positive patients, decreased the risk of dementia by almost five times (Tzeng 2018). Research is ongoing about using antivirals directly as treatment for Alzheimer’s, however results are not yet available.

Chlamydia and Alzheimer’s

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an intracellular bacteria that causes pneumonia. It’s in the same family of bacteria as Chlamydia trachomatis, the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted disease.

A recent meta-analysis reviewed the consistency of findings for infections in Alzheimer’s patients. In the study, the pathogen with the strongest link to Alzheimer’s disease was Chlamydia pneumoniae. Potentially, the risk of Alzheimer’s appeared to be more than four times greater in individuals that had been infected with the bacterium (Ou 2020).

Like with HSV, chlamydia infection in brain cells appears to rapidly induce an inflammatory state that increases production of amyloid-like structures (Al-Atrache 2019). Mice studies have shown similar results, but aren’t without controversy (Woods 2020).

Since chlamydia is a bacterium, antibiotics have been tried in Alzheimer’s patients to see if they can affect the course of the disease. However, results showed minimal to no results. Treatment failure may have been due to the fact that the antibiotics were ineffective at decreasing or eliminating the infection from treated subjects (Balin 2018). Research on additional approaches for clearing chronic Chlamydia pneumoniae infections in the brain are underway.

Lyme, Other Spirochetes and Alzheimer’s Disease

The bacterium that causes lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, is a member of the spirochete family of bacteria. The spirochete family also includes the bacterium that causes syphilis (Treponema pallidum) and common bacteria in the mouth that cause or worsen gum disease (Treponema denticola and others).

Spirochetes are corkscrew shaped bacteria that have a proclivity for invading brain tissue and causing latent infections. In syphilis, it’s well documented that the bacterium can cause progressive dementia, brain atrophy and amyloid deposition with similarities to Alzheimer’s disease (Miklossy 2015).

Studies done mostly by a single research group found that 91.1% of almost 500 patients with Alzheimer’s had evidence for spirochete infections from either brain or blood samples (Miklossy 2011). In the same research, there are suggestions that oral bacteria may be the most common spirochetes that infect the brain leading to dementia. Severe gum disease, which often includes spirochete bacteria, increases risks for dementia by a factor of three (Leira 2017).

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s

Another mouth pathogen often involved in gum disease has been receiving recent attention for purported links with Alzheimer’s. Porphyromonas gingivalis is a bacterium that produces enzymes called gingipains. These enzymes break down immune molecules (cytokines) involved in a healthy immune response. Patients with Alzheimer’s have been found to have gingipains in the brain plaques and tangles associated with the disease. In addition, mice given Porphyromonas bacteria develop brain infections with structural changes that appear similar to Alzherimer’s (Ryder 2020). Gingipain inhibitors given to mice with Porphyromonas infections in the brain decrease levels of infection and improve brain pathology. Human clinical trials are currently being pursued.

Conclusions

Based on all the evidence, it appears quite likely that infectious organisms play a role in Alzheimer’s disease. Unfortunately, most of these infectious organisms are quite common and avoidance is not realistic. For HSV, emerging evidence suggests prescription antivirals may significantly reduce risks of future Alzheimer’s development. However, full clinical trials are needed to verify the results. Antibiotics, at least at this point, do not have evidence of treatment efficacy, but this could change with more research.

Since exposure to these organisms is common, strategies to regulate immune function and decrease inflammation can play a role in reducing risks. A diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in sugars and carbohydrates appears helpful. Maintaining proper levels of nutrients, including vitamin D, zinc, selenium, magnesium and lithium may play a significant role. In addition, curcumin, tea, grape seed extract or other anti-inflammatories may help mitigate risks. For a review of potential treatments, you can see an outline of a talk I’ve given on Alzheimer’s disease here.

Really enjoyed the article on Alzheimer’s as an infectious disease. Wondering how this correlates to the Indian diet and people in this country having less incedence of this disease.

There’s a number of theories as to why Indians have less Alzheimer’s Disease. I’ve heard some claims that it could be due to larger amounts of turmeric in the diet. It’s hard to say if brain infection plays a part. I don’t know of any statistics on lower rates of gum disease or herpes-type infections in India, but that’s not impossible. It could also be down to genetics.

This is one awesome article post. Really thank you! Great.

Wow! Finally I got a webpage from where I can genuinely obtain helpful facts concerning my study and knowledge.

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Many

thanks.